Graduate students of the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education (KPE) hosted the annual Bodies of Knowledge (BoK) conference in May. BoK provides early career researchers, including undergraduate students, an opportunity to share research and engage in important conversations relevant to the field of kinesiology, sport and physical education.

Greg Wells, a renowned physiologist, best-selling author and peak performance expert was the keynote speaker. A former associate professor at the University of Toronto and a scientist emeritus at the Hospital for Sick Children, Wells is currently the CEO and founder of Wells Performance, a global consulting firm helping teams, schools and businesses reach their potential through improved health.

We caught up with several student presenters to learn more about their research and why it's important.

Second year master's student Kyle Farwell, seen here on the right working with members of the Waterloo Fire Rescue team, presented on his research into reducing the burden of low back disorders in the fire service (photo provided by Kyle Farwell)

Kyle Farwell, a second-year master of science student at KPE, presented on his thesis and a firefighter study, funded by the Centre of Research Expertise for the Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders (CRE-MSD).

“My research and professional interests center around reducing the burden of low back disorders in the fire service,” says Farwell. “I aim to help design and implement exercise and wellness initiatives that help firefighters gain the capacity to meet the overall demands they face on the job and in life.”

While the data analysis is in its early stages, the study's findings will help identify specific personal constraints, e.g., active and passive hip mobility, that influence movement behaviours related to fundamental spine mechanics and control. Furthermore, each participant will receive an individualized plan to increase, improve or integrate their hip mobility based on their data.

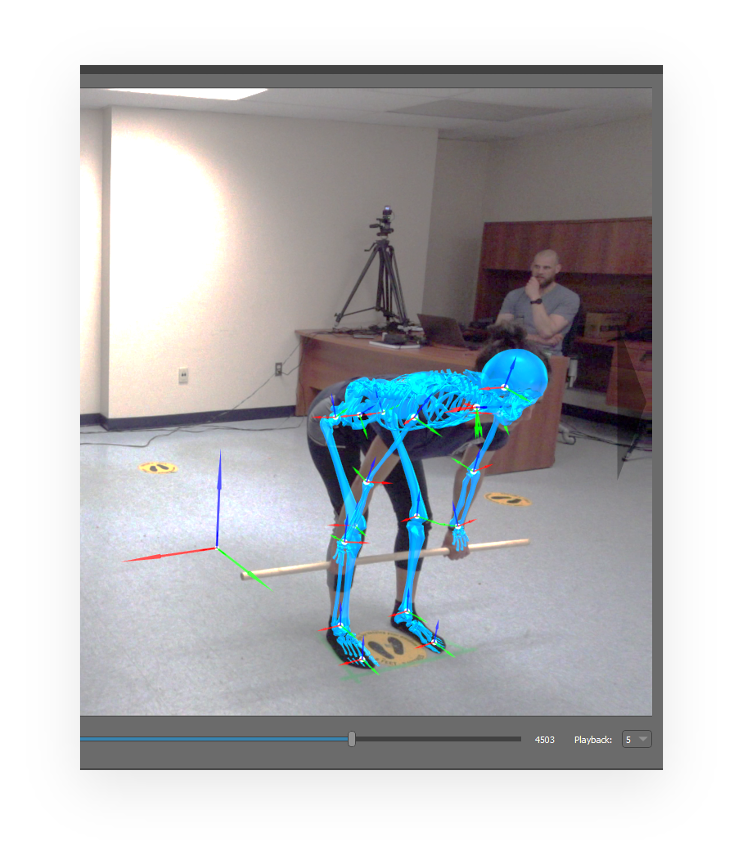

Farwell used state of the art motion-capture technology to accurately estimate the forces on the hip, a non-invasive way to retrieve research data

Farwell’s research supervisor, Associate Professor David Frost, is an education and scientific advisor to the International Association of Firefighters (IAFF) and will present results from this project to thousands of IAFF members.

“In addition to contributing to existing health and wellness initiatives in the fire service, we believe this work applies to all first responders and healthcare personnel involved in patient lifting,” says Farwell.

Students enjoyed a free lunch between presentations

Farwell's thesis examines the influence of constraining lumbar spine (lower back) motion while passively stretching the hip (stretching using external force) on active hip flexion mobility (ability to move using the strength of your muscles) in subsequent exercise tasks.

“It's considered best practice to constrain lumbar spine motion while assessing passive hip flexion mobility in a clinical setting,” says Farwell. “Furthermore, individuals have significantly increased their active hip flexion mobility when spine motion was experimentally constrained during a lifting task.

“However, little attention is paid to the lumbar spine position while stretching.”

Farwell found that constraining lumbar spine motion while passively stretching the hip extensors resulted in greater passive mobility increases (pre-stretch to post-stretch) than when the same participant was stretched without their spine motion constrained. However, the passive stretching intervention (constrained or unconstrained) had little impact on participants’ active mobility during exercise.

“The notion of (passively or actively) constraining adjacent joint motion while stretching a target joint is somewhat novel in exercise and rehabilitation settings, and it may provide benefits when stretching to influence movement behaviours,” says Farwell.

York student Sara Gagnon presented her research on the impact of consuming Greek yogurt after exercise on markers of bone turnover in overweight women

Sara Gagnon, a first-year master’s student from York University, presented on the effect of consuming Greek yogurt after exercise on markers of bone turnover in women who are overweight or obese.

“Bone turnover involves the trading between bone formation and bone breakdown,” explains Gagnon. “A greater amount of body fat can increase bone breakdown, which can weaken bones.

“With obesity increasing among young women, strategies are needed to increase bone mass, especially before the age of 50, when rapid bone breakdown may occur.”

While exercise can improve bone health, what is eaten following exercise may be just as important, says Gagnon. Greek yogurt, which is high protein and calcium, is expected to support bone formation and lower bone breakdown.

“My proposed research will compare the bone response to Greek yogurt following exercise compared to a high-carbohydrate snack in young women who are overweight or obese,” says Gagnon, who is working on this project under the supervision of York Associate Professor Andrea Josse. “These results will provide information on lifestyle changes to potentially improve bone health in these women.”

Muireann Heuchen shared a poster presentation about the research project into protein intake in adults with coronary artery disease undergoing cardiac rehabilitation while practicing time-restricted eating vs. those undergoing standard cardiac rehab.

Muireann Heuchan, in her final year of undergraduate studies at KPE, also had the opportunity to present her research project comparing protein intake in adults with coronary artery disease undergoing cardiac rehabilitation while practicing time-restricted eating versus standard cardiac rehabilitation.

While preliminary results of the study indicate that there could be a small decrease in how much protein people are getting when they start time-restricted eating, this is yet to be confirmed when all the data has been analyzed. Importantly, time-restricted eating did not appear to impact muscle mass, which is a welcome finding, according to Heuchan, who worked on the project under the supervision of Assistant Professor Amy Kirkham.

“Time-restricted eating has potential cardiovascular health benefits, but when people start time-restricted eating, they might inadvertently start to eat less or different kinds of foods, which can result in decreased protein intake, ” she says. “Protein is important for the development and maintenance of muscle, so we want to make sure people on a time-restricted diet are getting enough protein, and if they aren't, we can start looking into ways to help them eat more protein.

“I am looking forward to seeing if the trends I found continue when the study is complete.”