Cancelling, moving or boycotting the Beijing Olympics runs counter to the very purpose and history of the Olympic movement and places athletes in an untenable position, writes Bruce Kidd, professor emeritus at the University of Toronto Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education, in The Conversation.

With the Tokyo Olympics coming to an end, human rights activists are expected to step up their campaign against the 2022 Winter Olympic Games in Beijing in protest against the genocide of the Uyghurs and other Turkic-speaking people in Xinjiang, the colonization of Tibet and the suppression of democracy in Hong Kong. They will call upon the International Olympic Committee to cancel or move the Games that start in just six months, and if that fails, they’ll urge athletes to boycott.

As frightening as those human rights abuses are, they’re not likely to persuade the IOC or athletes to change their plans for Beijing. Cancelling, moving or boycotting the Beijing Olympics runs counter to the very purpose and history of the Olympic movement and places athletes in an untenable position.

Choosing a different strategy

Given the almost constant tensions in world politics and international sports, boycotts and threats of boycotts have almost been an accepted feature of the modern Olympics. The first occurred at the inaugural Games in Athens in 1896, when German gymnasts known as “turners” refused to participate because most of the events were British sport.

There have been feminist boycotts (British women stayed away from Amsterdam in 1928 when the IOC reneged on its promise to add 10 women’s events to the athletics program), podium protests against racism (Tommie Smith, John Carlos and other U.S. athletes in 1968), so-called recognition boycotts (Taiwan left in 1976 when the IOC refused to call it the “Republic of China”), anti-apartheid boycotts (29 African and Caribbean teams walked out of the Montreal Olympics in 1976 to protest a New Zealand rugby tour of apartheid South Africa) and Cold War boycotts in 1956, 1980, 1984 and 1988.

In 1936, an international coalition of socialists, labour unions and churches not only mounted a highly visible boycott campaign against the staging of the Games in Nazi Germany, but tried to hold a counter-Olympics in Barcelona. It was only cancelled when the Spanish general Francisco Franco led an armed attack upon the city on the morning of the opening ceremonies, starting what became the bitter, three-year Spanish Civil War.

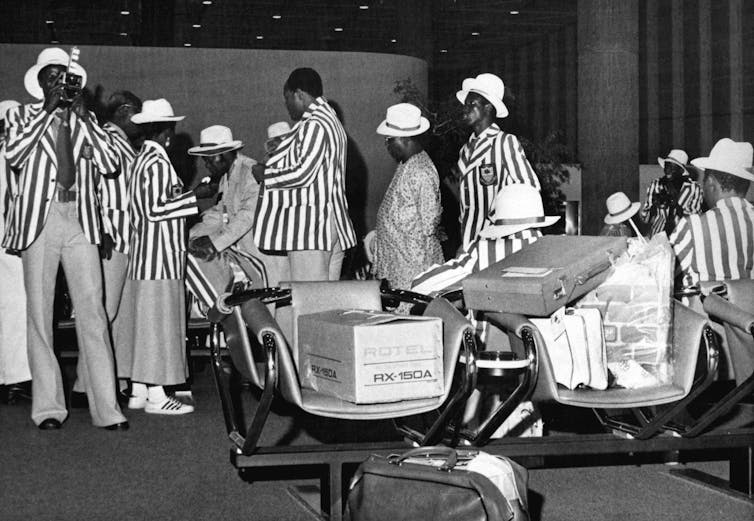

Members of the Nigerian Olympic team prepare for their journey home at Montréal’s Mirabel Airport after it was announced they would boycott the 1976 Olympic Games. The boycott came after the IOC refused to expel New Zealand from competition after its rugby team did a tour of apartheid South Africa. (THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Members of the Nigerian Olympic team prepare for their journey home at Montréal’s Mirabel Airport after it was announced they would boycott the 1976 Olympic Games. The boycott came after the IOC refused to expel New Zealand from competition after its rugby team did a tour of apartheid South Africa. (THE CANADIAN PRESS)While the Olympic movement is not indifferent to human rights, it seeks to bring representatives of every community in the world together for peaceful dialogue and sports — recognizing that there are very real political and ideological differences among nations.

To build such a big, inclusive tent, it makes few demands upon National Olympic Committees, the international federations that govern the sports or the host countries. It’s the sporting equivalent of the long-held principle of “non-intervention” in the internal affairs of nation states.

As the world has begun to contemplate the obligation of the international community to safeguard citizens from an abusive national state, activists are calling on the IOC to apply and enforce human rights upon National Olympic Committees, federations and host countries. That battle is far from won.

The IOC has been able to withstand boycotts because it selects its own members, a grossly undemocratic process that ironically has enabled it to stand up to the strongest governments. In 1980, in the face of intense pressure from U.S. President Jimmy Carter to cancel or move the Moscow Olympics, the IOC voted unanimously to go ahead.

A statue of Lenin sits outside of Lenin Stadium, the main stadium for the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. The United States and 65 other countries, including Canada, boycotted the Moscow Olympics in protest of Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. (AP Photo)

A statue of Lenin sits outside of Lenin Stadium, the main stadium for the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow. The United States and 65 other countries, including Canada, boycotted the Moscow Olympics in protest of Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. (AP Photo)While most athletes are concerned with human rights, an earlier generation learned in 1980 that governments, corporations and human rights activists are quick to volunteer them for symbolic actions, only to find that they’re the only ones who actually sacrificed something important.

In 1980, the government of Pierre Trudeau forced Canadian athletes to stay home, despite their strong objection, and then cut their funds afterwards. The oral history of that bitter experience looms large in the informal discussions about the proposed Beijing boycott currently taking place among Canadian athletes.

A way forward without boycotting

Is there a way for the Olympic community to attend the Games without legitimizing atrocities in China? As an Olympian and an academic who has studied the Olympic movement for decades, I believe there is.

Instead of the IOC knuckling under host country repression, as it did in Beijing in 2008 and Sochi in 2014, it should ensure that the freedom of expression now guaranteed in the revised Rule 50 should be respected during the 2022 Winter Olympics. Activists should insist that no one will be penalized under the revised rule.

Secondly, the IOC should affirm the importance of human rights and full intercultural exchange in the opening ceremonies and the schedule of events and meetings in the Olympic Village, as modern Olympic founder Pierre de Coubertin always intended. That would give athletes and others concerned about human rights the opportunity to express their views freely with other Olympic participants and their hosts without constraint.

There is Olympic precedent that needs to be remembered and strengthened. In 1936, when he arrived in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany for the Winter Olympics, IOC president Henri Baillet-Latour found the city plastered with anti-Semitic, Nazi propaganda. He immediately met with Adolf Hitler and demanded that the posters and flags be taken down.

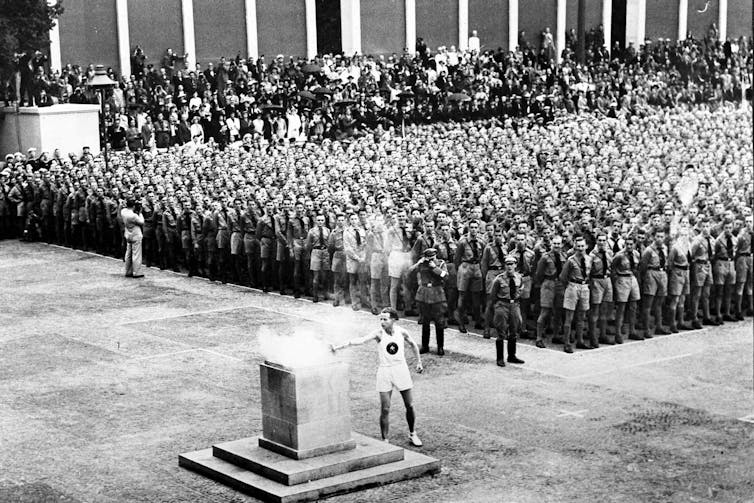

German Nazi soldiers line up at attention during the lighting of the Olympic torch at the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. (AP Photo)

German Nazi soldiers line up at attention during the lighting of the Olympic torch at the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. (AP Photo)Hitler is said to have replied: “When one visits a home, one doesn’t immediately ask the host to redecorate.” Baillet-Latour rejoined: “Yes, Mr. Chancellor, but when the Olympics is held, it’s not a national city but an Olympic city, and should be held according to Olympic rules. The propaganda must come down.” It did.

Baillet-Latour also established the requirement that the host country must recognize every participant duly entered by a National Olympic Committee, regardless of their background, a stipulation that ensured full participation in Berlin and during the Cold War.

In the end, the 1936 Games were a tremendous propaganda victory for Hitler, and the world lost sight of the safeguards won by the IOC. But an updated version of that strategy would be useful today.

The IOC should make it clear that while it’s grateful to China for hosting the Winter Olympics, the Olympic movement guarantees the right to free speech — including the condemnation of genocide and other abuses — within the Olympic precincts. Activists should support it.

It would be an important step on the long road to human rights.